Musing on Power - Tiffany

urban reconnaissance: “observe, assess and represent the urban context from a specific perspective, and to single out particular elements, rhythms or systems concurring in the production of the overall urban identity” (Tripodi).

The specific perspective I was given was names: “Investigate names given to places and streets or recorded in monuments: how when and by whom were they assigned? Which memories and culture they represent, how are they related with present life and culture? How names are related with colonial practices and / or post-colonial thinking?”

my explorations took me to power.

power city – the city is a field of forces, a territory of conquest and domination. It is shaped by competition, by individual and corporate appetites, by social claims and the ruling and intermediary presence of public institutions and constitutional powers. The distribution and confrontation of powers determine spatial development, concentrations of wealth and facilities, segregation and subjugation. Either manifest or obscured, power affects the way centres and centralities are created and related to one another, how peripheral and interstitial spaces are produced and how antagonistic and social movements take root in urban society.

Power sits within the appropriation section on the wheel.

reflections on power

Power is an essentially contested concept but I will use the understanding of power as a relation, not a resource to be distributed. A division exists in the philosophical literature between those who define power as power-over and those who define it as an ability/capacity to act, or power-to-do-something.

POWER-OVER

Power in the reconnaissance wheel, is conceptualised as a relation of domination, or power-over: an illegitimate, unjust and oppressive force.

Kaiser-Wilhelm Platz – sketches and photos from the reconnaissance

The square was named after Wilhelm I as there was a monument to him on the square. The monument was removed, yet the name remained. Wilhelm I was German Emperor from 1871 until his death in 1888. The notorious Berlin Conference of 1884-5 took place under his rule, organised Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, which formalised the “scramble for Africa”. The German colonial empire controlled colonies in German New Guinea, German East Africa (present day Rwanda, Burundi, and mainland Tanzania), and German South-West Africa (present day Namibia). From this era onwards, many Africans migrated to Germany.

Decolonial scholars in South America delve into the character of power (Quijano, 1989, Mignolo, 2000). The “coloniality of power” captures the continued substance of colonisation, well beyond the strict limits of colonial administration: in other words, decolonization did not eliminate coloniality, “it merely transformed its outer form” (Quijano & Wallerstein 1992, p.550).

POWER-TO

Power may also be positive. While power-over has masculinist connotations, power-to points to transformative and empowerment-based conceptions of power. Power is an ability, a capacity to transform oneself and others.

For Hannah Arendt, power is communal – it can only be practiced with others. She focused on collective empowerment and feels power’s capacity dissolves the moment humans disperse/do not act together in concert.

Audre Lorde proposes the erotic is a source of power-to (which I will be mapping in Lab 2).

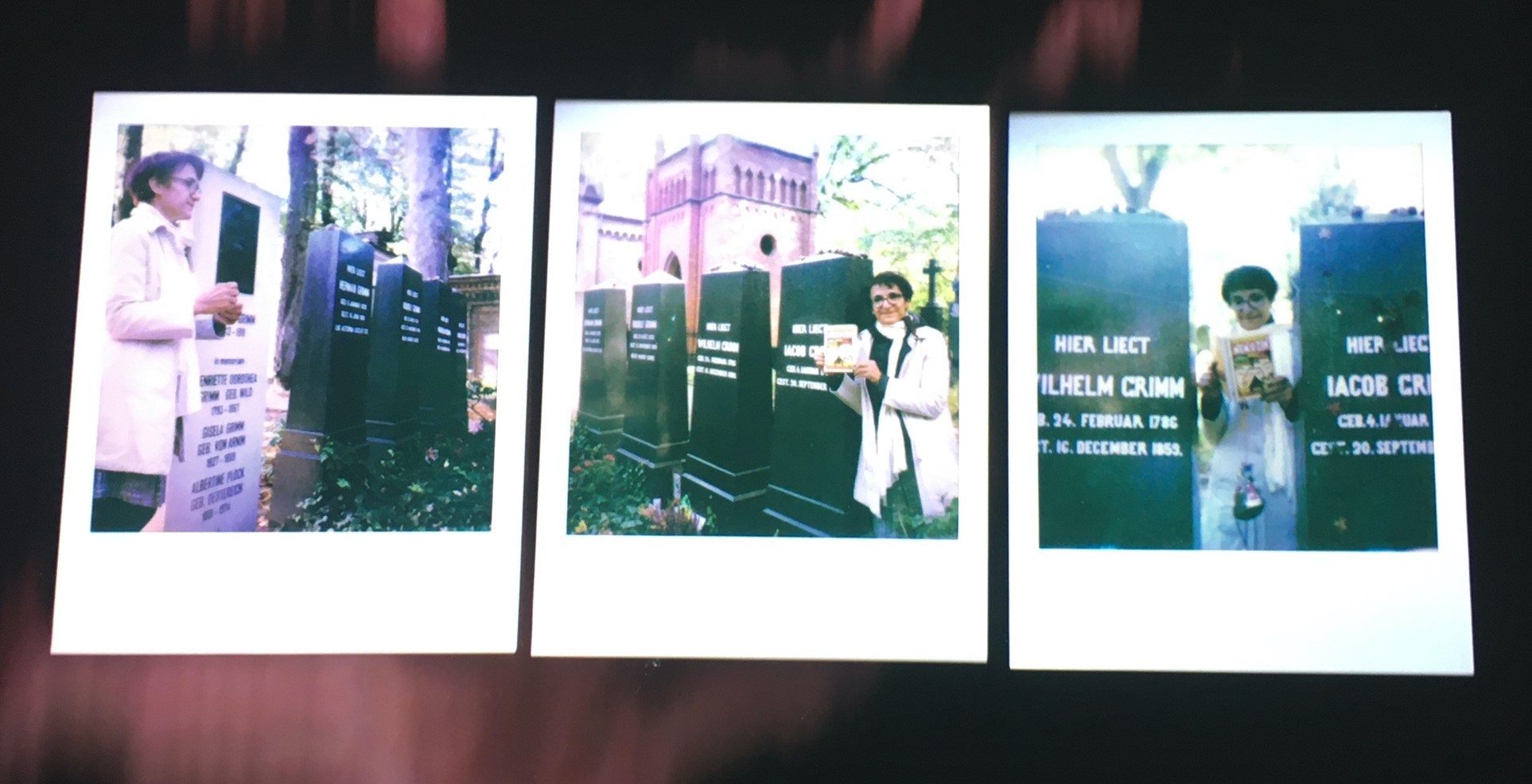

An example of power-to, in the realm of remembering, is conjuring silenced voices in the Alter St Matthäus-Kirchhof cemetery, Schöneburg. Ziyaret is a 12 min film essay by Aykan Safoglu, 2019, exhibited in Bethanien, Berlin (September, 2020).

“you can hear the words of those resting here if you read them from the silence”.

Aykan Safoglu explores boundaries between private and public memory and between loss and memory during a walk. The encounters he and Gülsen Aktas - a Kurdish activist, feminist, social worker and long-time friend – had with people like May Ayim, Ovo Maltine, and Birgit Rommelspacher, whose resting places lay in the cemetery, become testimonies to the persistence of those figures’ biographies and activist lives. By overlaying narratives via the graves of the Brothers Grimm, Heinrich von Treitschkes, and Friedrich Drakes, Safoglu asks which hegemonial logics are pursued by remembrance culture. Ziyaret is an aesthetic and symbolic moving-closer to the cemetery as an archaeological site: it makes visible forgotten and marginalised stories of migration, anti-colonial movements, and AIDS activism in Berlin.